In Pursuit of Paris: the Stories of the VAA Residence Cité Internationale des Arts. Part II

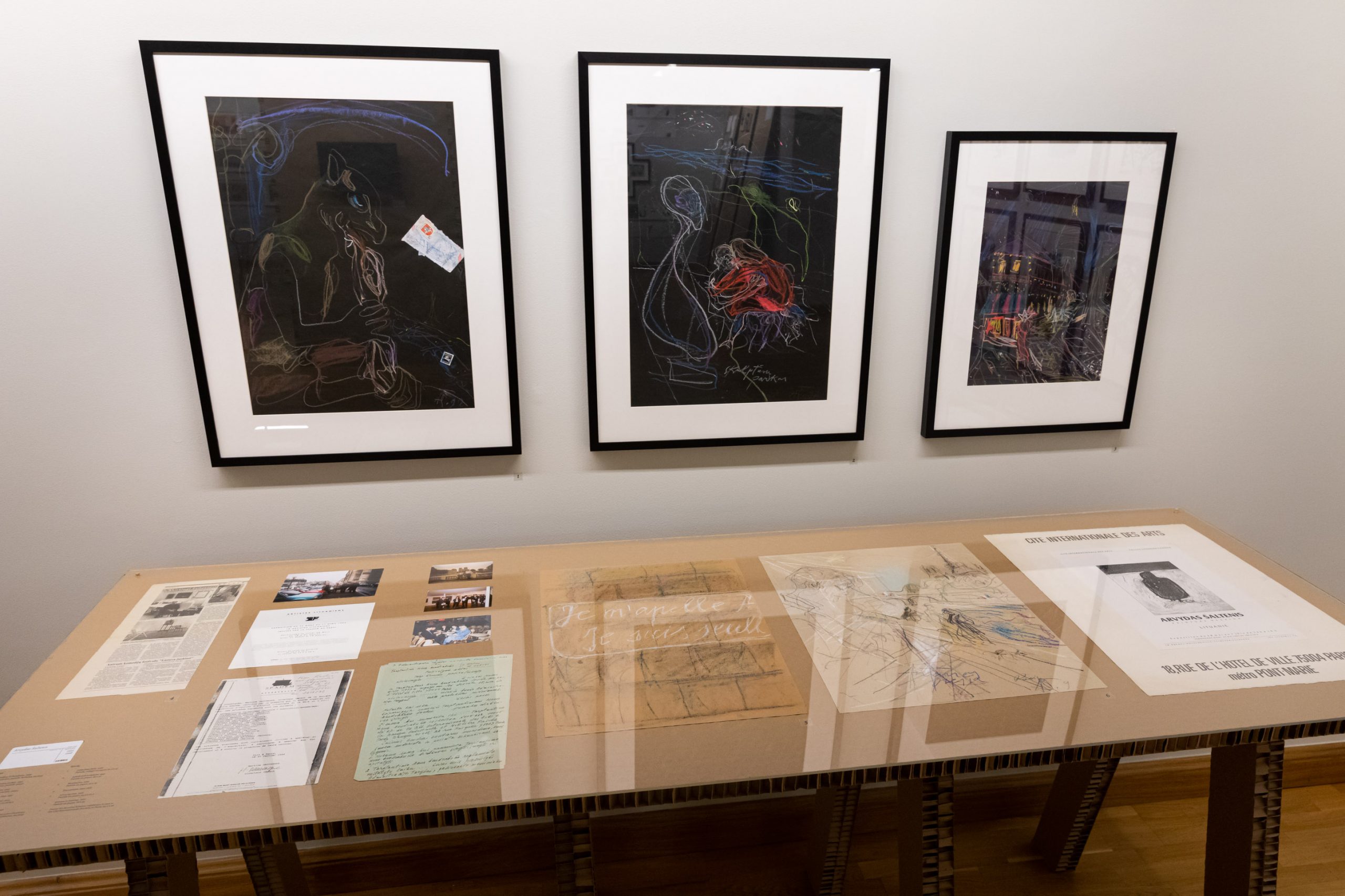

Arvydas Šaltenis

Impressions from Paris; or, How the Vilnius Academy of Arts acquired a studio at the Cité Internationale des Arts

The poem about the lonely Rembrandt’s pig feeder kneeling at the Sacré-Coeur basilica on the eve of All Souls’ Day renders the feelings upon returning to my Montmartre studio from the Louvre where I saw Rembrandt’s portrait of his son Titus.

In 1992, I had a residence provided by the Cité Internationale des Arts, staying in Paris on a scholarship by the Institute Français de Lituanie programme Courant d’Est. Every evening, when dog-tired after my wanderings of the museums and galleries I climbed the numerous steps up the hill, past its small squares with the converging rays of multiple streets, past the theatre building I knew no name of, but knew that some time ago Juozas Miltinis played there and learned the principles of European theatre. These were the paths walked by my teacher Antanas Gudaitis, and van Gogh before him, and many other great painters. I recalled the words by Ričardas Vaitiekūnas before my departure to Paris wishing me to step into their footsteps…

It was autumn, All Souls’ Day. That evening I went to the nearby cemetery and was surprised to see no candles burning. Only a policeman, blowing a whistle and crying fermé, fermé, put me out of the city of the dead.

I had a plan to visit all the galleries in Paris alongside with the museums, so I made notes of the exhibition opening times, curious to meet also the artists. In a couple of weeks I realized, that given the multitude of events it was hopeless and even useless idea. Just like everywhere, Paris was not immune to bad art and failed exhibitions. I myself started drawing on the streets, on the metro train, and the embankments of the Seine.

Nobody paid my stipend, instead, I was flung from one bureaucratic agency to another, situated in different ends of the city. In despair, at one of such places, I read from memory a French poem by Oscar Milosz to two female clerks and showed them a portrait of the Lithuanian poet who wrote in French. They were fascinated, and my beloved poet settled the matters of my life in Paris immediately. These poems ‘rescued’ me many times. The people, who lived and created in Paris and were connected to Lithuania, were my anchor when I felt sick for home and homeland.

I recall the Sundays with the Lithuanian community and their lunches after holy mass. Recall such people as the wife of the recently departed Algirdas Julius Greimas; priest Jonas Petrošius, Ričardas Bačkis (the brother of the wine, and I showed him our paintings. He gave us all kind of advice, wrote letters of reference to the galleries, and was still cross with Picasso, who had bought a 17th-century mandolin and cut it by half for his still-life. We got into such a trusting relationship that he brought out a portfolio with drawings, pastels, sketches of compositions: some kind of art counterfeiter was using them to paint copies of the artists of Paris school. The portfolio contained ideas for paintings by Modigliani, Vlaminck, Braque, and other painters of the time. After some years, I found that antique shop with its windows barred. The translator Gintaras Morkūnas became a member of honour of the group 24 and its supporter.

During my residence time, I was obliged to pay a visit to the founder’s wife Simone Brunau, then at the helm of the Cité des Arts. I presented her with a volume of Lithuanian art, I could see her exceptional attention to Lithuania as a newly independent country. I was entitled to and asked for a permission to organize, the next year, my solo exhibit at the Cité gallery. I arrived by car, my Moskvich, bringing along the paintings, Antanukas and Aldona. We could use a Montmartre studio again for the occasion. During the opening with the participation of the Lithuanian ambassador Osvaldas Balakauskas, Madame Brunau mentioned the possibility for Lithuania to have its own studio alongside other countries, universities or academies. I brought the news to Lithuania. Everybody looked at me like a dreamer, talking unrealistic things. Except for Viktoras Liutkus, who at the time worked for the Ministry of Culture and supported the idea. Seeing that the ministry turned a deaf ear on the letters from Paris and the term was about to expire, he gave me a call asking the Academy to step in. For good or ill luck, I was a freshly elected rector of the Academy and I rushed to materialise the then not much real dream of artists to have an atelier in Paris. It was summertime. I remember calling, from a post-office in Utena, the chairperson of the Seimas, Česlovas Juršėnas, whom I knew from the time of Sajūdis trip to Austria. We celebrated his birthday there. He recalled me too, and was easily persuade to change, at the Board of the Seimas, the purpose of the funding allocated to the Academy in the Law on the Budget Structure. Instead of eternal repair and roofing works, the funding was committed for purchasing an atelier in Paris in an extension constructed by the Cité Internationale des Arts.

For 26 years already, our artists stay there, paint, write and compose music. I only had another dream that each of the residents, when going to Paris, arrange it with the Cité gallery, to give an exhibition (not necessarily concurrent with the time of stay). This way we could ensure a continuous representation of Lithuanian art in Paris.

These disorganized memories of mine are just a drop in the history of our cultural relations with Paris, and of Paris – with us. This white and beautiful city (as I first saw it from the hill of Montmartre) has given so much to our culture and will do so in the future.

Arūnas Vaitkūnas (1956–2005)

Comet Hale-Bopp kept crossing the sky over Paris, while our stay was drawing to an end, making us restless and rushed. From time to time Arūnas would joyfully finger the book he bought in Paris. When I asked when we were going to see it, he would say, ‘It is impossible, see how neatly it is packed.’ He wanted to capture the time in Paris in such an odd way. Arūnas brought home his paintings packed in an equally neat folder. Unpacked and untouched, the folder waited in his studio all the summer. Rumours about some mysterious paintings from Paris started circulating among his colleagues. ‘It is packed so well, I do not feel like opening it.’ Then he would add with all earnestness, ‘Probably, in my thoughts, I still do not want to come back.’

Early autumn the painter Mykolas Šalkauskas (1935–2002) paid a visit to him. Arūnas told him about Paris, and over a conversation, he did not notice how he unpacked his works. ‘Šalkauskas said it is quite good,’ he said, adding that he should show the works in an exhibition, ‘because later on they will not be relevant.’ Yet Arūnas was very particular, as to where to show these works, insisting on presenting them in ‘neat frames and under matte glass’. ‘I do not want to show these paintings on paper carelessly, so I did not take part in the galleries exhibition staged at the CAC,’ he told a reporter from a daily.

In 1998, he left for Berlin and showed his Paris auf Papier at Giedrė Bartelt gallery. In 1999, he showcased the works at M. K. Čiurlionis National Museum, Kaunas Art Gallery. His exhibition time concurred with a show by the world famous painter Sigmar Polke. The works by the German artist were displayed in one room, Arūnas’ work – in an adjacent room. These two exhibitions, though very different, spoke to the viewers with strong voices about life in the world. Arūnas composed a short text for his exhibition.

‘It is a compensation of impressions gathered through the day. The abundance of concrete facts is drowned in a synthesis. A melted reflection of the environment. Each piece has concrete inspirations, yet during creative process, I withdrew into painterly areas. It is simply a totality of works Paris’97.’

From: Aušra Barzdukaitė-Vaitkūnienė. Toks gyvenimo kvapas. Kaunas: Bonarta, BalticSign, 2009, p. 135.

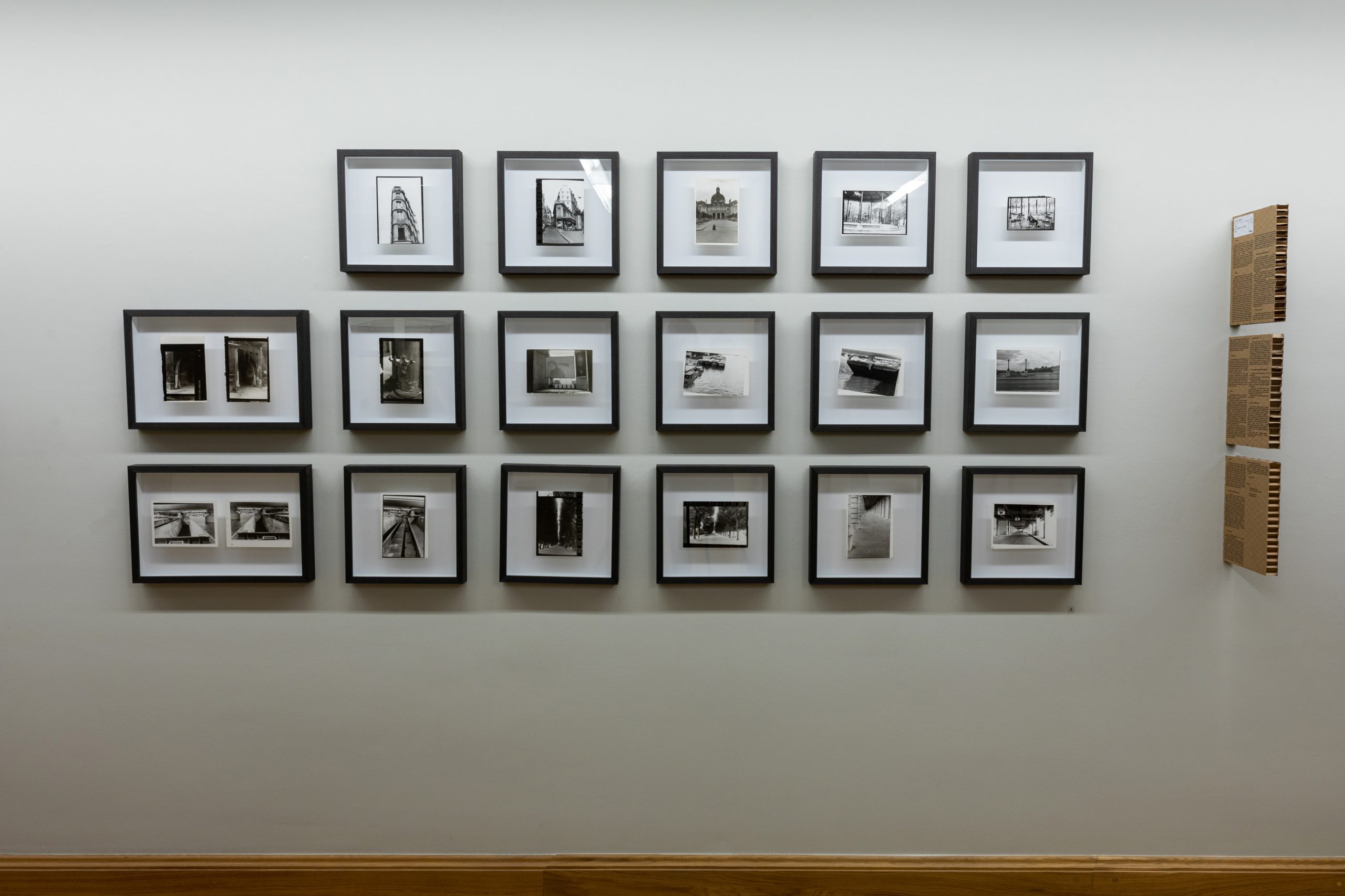

Aleksandras Vozbinas

Some aspects of painting from live in Paris

When starting, it would be good to spend in Paris at least a week or so and get used to it. It is important to overcome the dizziness and euphoria caused by the first impression of this wonderful city…

Only after a while, you can get back to your senses and start looking for motifs and places that would appeal to you. They are not necessarily views favoured by tourists, or those seen on postcards of Paris. By the way, images pleasing to the eye not always make the best material in terms of painting for future works…

The axis of Paris is the Seine River with the banks that stretch on for many kilometres. Yet only several dozen meters along the riverside reveal to your eye new aspects and shapes of things…

Just get down the steps that lead to the river and you discover new angles and takes of a seemingly familiar motif.

Despite its majestic size, Paris is indeed full of quaint corners, I would say, of an intimate atmosphere. I should also add that light in Paris is very inconsistent, varying with weather patterns. Sunshine may within seconds turn into rain with gusts of wind and vice versa. Thus, the same motif sometimes transforms into several pictures within a short spell…

Grupė „Baltos kandys“ (White Moths group)

(Austė Jurgelionytė-Varnė, Karolina Kunčinaitė, Miglė Lebednykaitė, Rasa Leonavičiūtė, Laura Pavilonytė-Ežerskienė, Julija Vosyliūtė)

Illegal life. Cité Internationale des Arts

The room is only a double, yet there are five of us in it. I mean, legally it is only for two persons. Yet we are from Eastern Europe, and why keep it a secret? The ability to find a way out and adjust under almost any circumstance is in the DNA of our country’s experience. Artistic contents of our wallets, typical of many a junior artist, also determines some of our possibilities. The amazing administration of Cité Internationale des Arts met only a couple from our rather large party, while the entire group then crept into those tiny rooms, most likely witnesses of many similar adventures. We inflated our sleeping mattresses and set up our cosy bunks.

Well, no other way around. Once you choose the fate of an artist, the advantages and the downsides of this lifestyle come in the same basket.

Having draped the huge, almost the size of a shop window, panes with dark curtains, we settled by the table, admiring through a slot in the curtain, snow falling on Paris, a rare view in this city. We treated ourselves to some stinky cheese, red wine, and several long French baguettes, with poppy seeds and with sesame.

‘To Paris, to us in Paris’, one of us saluted in a small voice.

Nobody wants to be too loud, as what if someone drops by and asks us to vacate the rooms. The only choice for us would be to join the local homeless sleeping in their cardboard boxes on the street. We noticed some of them under the roofs of the Cité.

‘To our future exhibition,’ somebody else picked up in a stronger voice.

The stinky cheese stank to high heaven and its mould was green.

‘To our gang, to our successful settling in Paris, hurray!’ You cannot just say ‘hurray’ in a small voice.

‘Hey, Moths, do you realize where we are, in the very heart of Paris, this place is worth a million, and just fancy us living here,’ somebody else was brimming with enthusiasm.

The crust of a baguette is crisp, yet inside it is soft and aromatic, and it goes very well with the stinky cheese.

‘Tomorrow we are to put up our artwork in the gallery just round the corner, do you get that?’ somebody else of us stepped in at the top of her voice.

‘Yes, one more thing we could use is an orchestra, but it’s high time to go, Paris is waiting, and in twilight it is even more beautiful.’

From: Karolina Kunčinaitė. Klajonių paveikslai. Vilnius: Tyto alba, 2006, p. 118-119.

Dainius Liškevičius

The Stereotypical images of death are three objects created in 1995 when I studied under Prof. Petras Mazūras at the Department of Sculpture of Vilnius Academy of Arts. The work was first exhibited same year at the Student Art Days, dedicated to the 120th birth anniversary of M. K. Čiurlionis. My work was awarded the 2nd prize and a month-long residence at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris. The exhibition also includes three documents bearing witness of these events, among them, a letter and a reference to another work, the French baguettes created specifically for this exhibition.

Darius Žiūra

There is that flower that grows in South Cape. If a human sees it blossom, he loses his wits. At first, this person will behave similarly to a cat treated to valerian drops. He keeps rolling around it, smelling it, stroking its leaves with trembling fingers. He cannot understand what is happening with him. He masturbates to the bloom, uproots the plant, puts it into his mouth and swallows almost without chewing.

When the flower reaches his stomach, it spreads small growths similar to soft needles, which start tickling so badly, that this person starts vomiting and throws up all that he has eaten during three previous days; he continues vomiting blood, and once all of his blood is wasted, he dies.

After a while, small yellow sprouts appear from the vomit. They reach to the sun and become stronger. Many of them are smashed by animal hoofs, bulldozer tracks; some end up in collectors’ herbariums. Most perish killed by pollution. Only individual specimen succeeds to mature and blossom.

According to science and medicine, this plant is extinct.

From: For Beauty. 3rd Exhibition of the Soros Center for Contemporary Arts – Lithuania. Vilnius: Soros Center for Contemporary Arts – Lithuania, 1995.

Eugenijus Antanas Cukermanas

Portfolio de Paris

These are the drawings done in Paris. Is it necessary to go to Paris to create one or another piece? No, it is not. Is it necessary, having gone to Paris, to work? Having in mind the fact that you are not doing traveller’s sketches? No, it is not necessary. Yet, why is it not necessary?

No matter what, but a separate studio in the Cité Internationale des Arts, on the banks of the Seine, facing the Île Saint-Louis, offers a perfect setting for work. It encourages you to work. Here you rub shoulders with plenty of artists; in fact, you meet no one else but artists; exhibitions as well as concerts are held.

On the other hand, this imperial city imposes itself on your person: you feel dwarfed by its spaces and distracted by its wealth. I started acting as if my personality had split into at least ten alter others. One was admiring the palaces and churches, as I had studied architecture a long time ago. My second ‘self’ rushed to see art in the museums or galleries. Yet another I was sifting through the treasures of an antique bookstore. The fourth ‘I’ roamed the streets, the fifth one was drinking wine by the riverside. It was only my tenth ‘self’, supposedly, an artist, who was in no hurry at all.

Eglė Ridikaitė

Paris. Cité Internationale des Arts. 1996

The beginning

It all started when Orūnė Morkūnaitė and I won a couple-of-month sojourn in Paris as a prize from the Student Art Days. How we rejoiced. That must be something fantastic; ahead of us was a fabulous voyage into the unknown: a trip to Paris, the same one I had never dared hope of seeing. It was like that forbidden fruit, familiar, tempting, yet also out of reach. We knew it from postcards and film, from books. A Mecca of all artists, and I could get to see it? The city of van Gogh, Gauguin, Utrillo, Rodin, well, everybody, even George Sand walked its streets. I was going to see it; I was going to see Him. It was when our journey started, the journey to this different world. I immediately got onto a month-long daily crash course of French.

The travel

All that packing and repacking: what to take and what to leave? Detergents, cheese. Travel by bus took a full day, if not longer. It was quite an adventure. The German customs wanted to check our backpacks in the lug- gage compartment. No chance they would pick another person’s belongings (mine was an orange, Russian-made mountaineering rucksack). I was asked to show what was inside. It took place in the middle of the night. Unpacking for them was an easy ride, but to fit everything back proved a challenge. (Thanks to Ramas, a professional packer, the rucksack held quite a lot of stuff). With two drivers, I was struggling to repack, yet there was too much of everything. Our hands were shaking too: we had no time to loose, pressed by the schedule. With great difficulty, we wedged everything back and headed Europe-wards. I felt slightly apprehensive, not knowing where I was going and what was in store. At least I knew that Orūnė, who had arrived last night, and Darius Žiūra were to meet me. I knew I could not miss my stop. The city was so huge. We connected as planned, it worked out all right, but I had another course of action in case I failed to get off at an agreed place or they failed to show. The city was dazzling indeed, an entirely different world. A place you long for, yet it also scares you. A nocturnal Paris it was, a jazz cafe or a club, with a black musician playing stunning jazz. Such was my first night in Paris, crowded and adventurous. That was how I came to know the city of dreams. In the beginning, we had to experience the menacing atmosphere of the megacity, the feeling of being unwanted and lonely. It was one of the weirdest early days of the haunting premonitions that they would realize that you – we – were missing only when the time of our stay was over. Then only they would step into your room to find a dead body after a couple of months. Such were the thoughts we shared with Orūnė roaming Montmartre on one of the early days. A French fellow, a visitor the night before warned us to be careful and left us apprehensive. He also told us all those horror stories. The next day we were scared to step out. We felt like being stalked and everyone watching us. There was also this Arab man, shouting something to us in Russian, perhaps nu devochki.

The joy of recognition, the joy of discovery

The first joy was of recognition – of places seen in movies, now rediscovered in reality. It is unbelievable, that feeling of déjà vu. I especially relished in the Pont Neuf and the point of the island (at the time my most beautiful movie was Les Amants du Pont-Neuf by Leos Carax featuring Julliette Binoche). It was one of my favourite spots. Who could describe that gigantic city, the smell and the freshness of the river. The Seine is the veritable vein of the city. The ultimate thing. The Queen of the city. Every night we went strolling by the riverside to consummate our day. The river absorbed all our fatigue and restored us to power; it was the first confidante of all our secrets. Nothing can equal these long promenades down the Seine. Especially the early morning walks, when mist is still lifting above the river and the city is still deserted. I took a special effort to get up with early birds to absorb the beauty of the empty city, when they take out coffee tables and arrange chairs for the day (my first lesson in beauty in a Parisian style). I walked under the bridges where the homeless with their dogs lived. These were their abodes. People were freely sipping wine, they were happy, and one could feel real freedom. The river- sides filled with the barges, each one a place of an individual life. The bouquinistes. Passing by, I always tried to unearth something very old from these stalls. This postcard with crosses, did I find it buy from the bouquinistes? I can no longer recall. Perhaps, everything looked a little bit beautified (now, after twenty-four years, I have a different understanding of the homeless. As well as of freedom.)

A smiley

My present memories, when I have them, are of broad expanses of sunshine and the glowing white stones. It was a tightly packed time. You arrived into a different world, not simply to spend time, to look around, but to learn. I did not feel like sleeping long, aspiring to see as much as possible. At the time, we were only preparing to become real artists and everything still seemed ahead of us; and we felt of being capable of everything and everything seemed to be in the future. Everything – well, maybe not completely. (These days I would use a smiley here, the one that Vilma taught me to love.). You drank knowledge like water, trying to go into the very depths every time, to feel the pulse of art. Also the pulse of Paris, the grand city of artists’ dreams.

The first month

The first month was probably just the time of get- ting to know Paris. Places to go, things to see. Darius Žiūra advised us of many things, what to visit, how to behave, he happened to spend a month in the same studio exactly a year ago. The studios were quite an entertaining place, full of folks. Perhaps we were cramped for room, yet every- body wants a place to stay. All the residents contributed something individual: their stories, impressions, things they saw and recommended to see. This way the information and impressions multiplied. More people could see Paris. Thus, it was good. Such was our first month, when Orūnė and I were mostly together. Afterwards we felt like working on our own, preoccupied with our graduation projects. We had to realize them after return from Paris. All we saw, we tried to keep in our heads. Afterwards, we started taking turns to work in the studio and to explore Paris and its exhibitions. Such way we could stay every other day undisturbed with our thoughts and work. We really could not get relaxed about our diploma projects.

Letters

Letters were this most important thing. They are the means of communication. Perhaps, they are also the means of reflection, of discussion with one’s self, and of recognizing what you want and what you feel. As it was the very beginning of my love relationship with my dear little man, the very first year, the separation was especially difficult. The writing of a letter, going across the Seine to the post office to buy stamps and to post the letter was such an enjoyable ritual. Happiness was also anticipating an answer when coming home through the main entrance. I would peak a look at the post box, e.g., a shelf that held our letters arranged according to room numbers. We also had our slot and knew where we to look, even without entering, to see whether there was a white corner sticking out. I also had an Indian friend who waved to me, letting me know that a letter had already arrived. He did so as he wanted to get a post stamp – as a collector, he hunted those unseen by him post stamps from an unknown, strange, faraway country. Probably, it was the way that letter writing and words found way into my art after Paris. Though not immediately, yet it was there that I understood they could also be transformed into painting. Where I fail at communicating through painting, words can supplement. That, indeed, is rather significant. As well as realizing that every word matters, it is not something you pick up and drop. It communicates a feeling. From these post boxes, I collected the idea of writing. I would have liked using it in my graduation project, but it happened later, after my graduation.

The Centre Pompidou

It was Orūnė’s and my home. I have the feeling we went there daily. If not to see an exhibition, then to watch a film on art, we tried to cover their entire collection of films on art, to list through all of their art books. That was so great, a plethora of information. We spent the day at the Centre, evenings by the Seine or simply hanging around the museum, listening to street musicians, waiting for Darius and Vaida (Žiūra) to finish their drawings to make money. Sometimes I had to act as a model in order to attract clients. They tried to convince me: come on, give it a try, you can draw and you should be good at caricatures. Yet I never mustered the courage for that, though once I was very close. Perhaps that would have been an interesting experience, the overcoming of the fear of people and getting paid for your work.

Things I failed to do, to visit and to see

I did not try drawing portraits on the street, but I do not grieve that so much. I did not visit the Picasso Museum, though we lived in the vicinity, for that I am sorry. I did not go to the top of the Eiffel Tower, I was first waiting for Ramas to come down, hoping we would ascend to the top together, yet when he came over and we made plans to go, it was pouring with rain. We never visited the Tour Eiffel. The Notre Dame Cathedral. We passed by almost every day, and we really saw it daily, as we lived across the river, right in front of the Cathedral. Perhaps repair works were on the way at the time. I learned a lesson that you should not postpone anything, as there may be no next time.

Paris – the city of love

That also happened to me. I talked to my dear little love in my thoughts (over the phone, too, and I keep an entire collection of phone cards and aren’t they beautiful) everywhere I went, even though he was not next to me. I wanted to show that wonderful city to him too, when there was such a great opportunity. Yet I had to find a way of bringing him in, as at the time we needed visas. Somebody had to write an invitation. Every day I kept thinking whom I should call, who knew whom. There were plenty of phone calls and stress, especially to me, as I cannot talk effectively over the phone. We received help and an invitation from Jonas Petrošius, the priest of the Lithuanian Community of Paris. Great thanks to him for having trusted and invited a young and unknown to him fellow. When Ramas came down, we went to see the priest, to introduce ourselves and to thank him for trusting us. A tiny flat, a little man, in a huge city, as Ramas put it, exiled to Paris and forgotten. Perhaps he was joking.

Food

It is an interesting topic indeed. We cooked at home, and tried all from the shelves of special height (we did not have plenty of money). Gorgeous cheese, salad, wine and, of course, the crunchy baguettes sold in those tiny boulangeries. For my birthday, I received an avocado as a present from the girls. We did not know how to eat it – we smelled it and tried it in small bites. There was no Internet and no way finding out, so finally I used it for making soup. It was a different soup, but we survived, smiley. We missed potato pancakes badly, so Ramas brought a potato grater from Vilnius, as you could not get one in Paris. We did make potato pancakes. Now it looks funny. Now it is different. It was interesting to see what people eat in restaurants; sometimes you could see that through the windows. I was interested in mussels and amazed that someone should eat so many of them.

Attempts at seeing Chartres

When Ramūnas joined us in Paris, we decided to catch a ride to Chartres to see the cathedral – it was interesting. Somebody said it was best to stick one’s thumb by an exit to the highway. Exactly that we tried to do. Yet reaching the highway is nothing simple – it is quite a distance. We got somewhere to the outskirts of the city – maybe as far as the metro line took us, I do not really recall. We disembarked and found some kind of the road – we were told it was an exit to the highway. Then we got hold of a discarded cardboard box, wrote ‘Chartres’ on it and put up our sign. Yet nobody stopped to give us a lift, instead the drivers showed us some hand signs. We decided to get to the highway or a gas station, I no longer recall. Maybe there we would have more luck. We walked down a loop exit leading to the highway. I do not know what befell with me, yet when I saw that big highway, I said, ‘I’m running down’, or maybe it happened to fast for me to say something. Then, suddenly that horrible squeak of the brakes, the sliding, the cursing… Afterwards we sat in a meadow for a long time, saying nothing, then promptly returned home, many things have erased from my memory. We locked the door and stayed put all day, at least I did. Alive.

2016, Paris

A present on my 50th birthday: two nights in Paris and a gorgeous dinner. Early morning. A cup of coffee with a croissant in a café and a window seat. Musée d’Orsay, where to next? Maybe, downtown. I stepped into the Notre Dame Cathedral. Then I headed towards the Centre Pompidou, Cité Internationale des Arts. It is interesting when you know and find all without a map. Turn the corner, and you’ll find this, and round the other, that. Maybe only the chain grocery stores changed their names, but remained in the same place. Now round this corner, there should be a photography gallery, and yes, that is correct. I did not visit the Tour Eiffel or the Picasso Museum – I did not feel like going there alone. I strolled along the Pont Neuf, then sitting on a stone bench of the bridge, wrote a letter that I never posted– because it was written to either myself or my little love – since it is Paris, the city of love. I spent some time at the tip. Then, my dinner – I ate more mussels, really more then I saw the real French eat in a restaurant window ten years ago. I also met the beautiful Marilyn Monroe with the same wind-blown dress, performed a role of an artist at a night café, in the morning, I got acquainted with the real macarons and headed home.

Thank you, Paris.

Giedrė Jankevičiūtė

A short note on what Paris is to me

My first visit to the Cité des Arts took place in 2000. At that time it was a challenge, the airfare was draconic. I received a tiny stipend from the Institute Français de Lituanie, however, I took a bus instead of paying for a very expensive air travel (Rynair and other cheap carriers started service from Lithuania only in 2010). We took a bus to France with the philosopher Nerija Putinaitė travelling on scholarship to Poitiers University. Happily, we headed the same direction. Otherwise a day and a half on an airless bus with the future cleaning ladies (unaware of Europe’s geography they disembarked at night somewhere in Germany) and the dealers in god-knows-what, knowledgeable in all black markets worldwide, on their way to Marseille (after crossing the border of France they were asked to get off by the young men and women of a mobile customs group) would have looked different from a simple and funny adventure.

At that time, I absorbed Paris greedily, willing to learn everything – the way one movės around the city, the local eating habits, places and stories. From a baguette to pate and the Centre Pompidou, from the Tour Eiffel to Opera Garnier, from the galleries in the 4th and llth arrondissments recommended by Paulius and Svajonė Stanikas to a romantic museum of Maurice Denis set in an elegant and frozen-in-time Saint-Germain-en-Laye, almost in the suburbs of Paris within a half-an-hour ride by the RER. Together with the conservators from Kaunas who brought M. K. Čiurlionis to the Musée d’Orsay, I could explore the back stage of the gigantic temple of art. On my own, I retraced the routes of Lithuanian artists from the Gare du Norde to Quartier Latin and to Montparnasse academies, to the école des Beaux-Arts and the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers. I subsequently described them all in my book Art and State: Artistic Life in Lithuanian Republic, 1918–1940 (2003). I met the print artist and intellectual Žibuntas Mikšys. We drank wine and ate cuscus with Žiba and Petras Klimai at their cosy place on Rue Oudinot. I travelled home by train via Berlin where I took part in my first big international conference and for the first time in my life tried to use a bank machine. With no success: I could not figure out how to operate it. I lost my bankcard, but gained confidence, as I managed to cope with the situation.

In 2008, I waited for my second stay at the Academy’s Paris studio as if it were a date with an old lover. It was fantastic. That time I could freely indulge in Paris. It was not a relaxation in any sense of the word, however. Daily I covered distances longer then pilgrims on the Way of St James, managing to absorb and experience even more than the first time. Yet all went smooth and easy. At the Jacques Doucet’s library I felt at home, found plenty of materials for the book I was working on, and learned myriads of new interesting things. At the time, the library hosted an exhibition of Sophie Calle. I had not previously seen any exhibitions of contemporary art in spaces not designed for showing art and I liked what I saw. In the spring of 2008, two legends of contemporary art from the USA visited Paris: Richard Serra was on at the Grand Palais and the Jardin des Tuileries, and Patti Smith at the Fondation Cartier. At the Cité I received personally very dear visitors. It was so nice to share a baguette, pate, cheese, and Pierre Herme pastries, the Rue Mallet-Stevens art deco architecture, the redesigned exhibition of the Musėe de l’Orangerie and always the same Nissimo de Comondo museum, to look for modernism in the streets of Boulogne-Billancourt and to hunt for Corbusier buildings in the town and its outskirts. A wave of unexpected warm weather brought along the excitement of the picnics by the Seine, the gardens of Giverny and the refined beauties of Fontainebleau. I was convinced that Paris is boundless and inexhaustible, but it is better to try it in small bites instead of gobbling it greedily. There is no universal recipe how to build an acquaintance with the place, but if someone aspires for lasting memories, it takes effort. Paris is not in a rush to reveal itself and offers nothing beyond things on the surface: tasty food, wine, the elegance of its centrai part, impeccable greeneries, glittering shop windows, boat trips on the Seine and the highlights recorded in the guides. It is more than enough for the first acquaintance, but Paris is so much more. Life at the VAA studio gives one an opportunity to experience all that. I will therefore never stop praising Arvydas Šaltenis, Osvaldas Balakauskas and other politicians and functionaries who provided permissions and the money to buy the studio. It is a single good thing that happened to Lithuanian culture at the dawn of the country’s regained independence.

The items presented for the exhibition come from my second, 2008, stay at the VAA studio Cité des Arts. On the eve of my departure, I got hold of my first laptop, a relatively light Toshiba, thus equipped, I felt myself ultramodern and independent. Yet the Internet connection at the time was a problem in Paris. At the Cité the price for this pleasure was sky high, it was insignificantly cheaper at the nearby Internet cafė, yet there one had to queue. In order to maintain my connection with the real world whilst exploring the riches of Paris museums and libraries, I acquired a TV antenna with a tiny receiver in a USB key. When I plugged it to my computer, I could watch French television and the BBC news. It was very practical as it also helped learning the language. I roamed Paris with the Blue Guide, which is considered the classics of all guides. The era of smartphones was only dawning, and very few people had them, while the time of the Google maps was still to come. The Blue Guide has everything a tourist needs: maps of the town and its parts, diagrams of public transportation, descriptions of streets and architectural monuments. I am not going to give up this guide even now, as there are things that can be found faster and easier in a book than on the Internet. Especially ifyou want to see how a particular detail connects to the whole. The brochures from the exhibitions I saw in 2008 as well as the cultural routes document some of my horizon-broadening experience. Some of these experiences and knowledge found reflection in the exhibitions I subsequently curated and the texts I composed. And, of course, my paper ticket of the Jacque Doucet Library of Art and Archaeology (now this superb library is part of the Institut National d’Histoire de l’Art (INHA)). It is the main document of my Paris visits besides my AICA membership card, which grants free tickets to museums and exhibitions and allows skipping queues to museums and exhibitions whenever one has to queue. These two documents were more important in my Paris life than my passport. In other words, while in Paris, I am primarily an art historian, curator, a professional of the broad, varied, deep cultural field. This also contributes to my exceptionally good feeling in this city.

1 Goštauto st, Vilnius, Lithuania

+370 5 261 6764.

kasiulio.muziejus@lndm.lt